- Home

- Rachel Ricketts

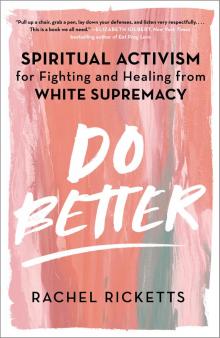

Do Better Page 2

Do Better Read online

Page 2

No matter who you are, my teachings will make you uncomfortable. We spend so much of our lives evading challenging or conflicting emotions. Controversial topics like racial justice are ripe grounds for checking out, but I urge you to resist that temptation. If you want to create a world where all humxns can be free, then I need you to increase your tolerance for the hard shit—hard emotions, hard conversations, hard decisions. No matter how mindful I help you become, this book is not going to solve white supremacy (I wish!). It won’t heal internalized oppression or make you an activist or an ally, though it will absolutely aid you in acting in allyship. It is simply a start. Even if you’re decades in. I am arming you with heart-centered tools to put into your ever-expanding toolkit for doing this work, day in, day out, for the rest of your life. You will be stretched well past your comfort zone. But you’ll be left feeling more supported and empowered in your journey to better show up for yourself and the collective in the ongoing war against white supremacy and, most important, in tangibly supporting BI&WoC worldwide. In doing so, you are helping to free the hearts, bodies, and minds of us all.

I’m not here to “tell” you anything but rather help guide you back to a truth you’ve always known. Back to yourself. Everything you need to do better already exists within you. What you read here will serve as guidance based primarily in my personal and professional experiences. Still, much like you, I am a learner still learning life’s lessons. This is not work to get “perfect”: I have not and cannot do it perfectly, nor can you. Perfection is an agent of oppression, so let us release ourselves from that expectation. There are undoubtedly elements of this book I’ll later learn caused harm. I welcome learning more so I too can do better in the future. I invite you to do the same. You will still fuck up, as will I. You will continue to cause harm, but you will have tools empowering you to engage critically, see beyond the lens of whiteness, and minimize and rectify white supremacist violence from here on out. To continuously do and be better. Not perfect.

You may be scared, you likely have apprehensions, but racial justice requires each and every one of us. Lives and livelihoods are on the line; the earth as we know it is at stake. No matter where you are in your racial justice journey, you will find something here. A learning or unlearning. A sliver of hope and cementing of truth. I have poured my heart out onto the page for you to live and breathe these experiences alongside me. So you can witness me and, in doing so, better witness yourself. This is my personal invitation to a brave space. In the words of justice doula Micky ScottBey Jones, “we all carry scars and we have all caused wounds,” so “there is no such thing as a ‘safe space.’ ”1 But here, as we move through this work together, I invite you to be brave. And vulnerable. To lean into compassion, to stretch past your discomfort, and to prioritize all those rarely prioritized elsewhere.

By guiding you through an internal exploration of your role in perpetuating white supremacy, anti-Indigeneity, and anti-Blackness, and providing heart-centered tools to support you in moving through the grief that inherently arises as you do so, this book supports BI&WoC in healing from internalized oppression and racial trauma, white women+ in addressing their racism, and all women+ in rising up to free themselves and the collective from global systems of oppression.

This is a book to read and reread. To take at your own pace and digest as you need. It is a loving yet challenging call to action. A call to do the deep inner work that precipitates any external or collective shift. An active opportunity for you to acknowledge and accept yourself and your role in perpetuating white supremacy for what it is. An awakening that is urgently needed to unify a divided world and ensure the future of humxnity as a whole.

* * *

I write this from a deep and profound well of love. For us all. My love includes anger. And this loving anger fuels my resolve for us all to both be and do better.

A NOTE FROM ME TO YOU

Any discussion of white supremacy is loaded and rife for misunderstanding, which is #notawesome, so before we dive in I hope to make clear a few key points unpacking my approach and perspective:

#1—There is a glossary of terms at the back of the book that I highly suggest acquainting yourself with now. Language is constantly (and quickly) evolving, so you may find some words or acronyms a bit overwhelming at first. That’s okay! From here on out I’ve put an asterisk (*) next to each word from the glossary the first time it appears in the text to help you get better acquainted. Either way, when you come across something you don’t understand, chances are it’s in the glossary, but please do research them further on your own as well. The intention is always to foster your own critical engagement as you read, learn, and unlearn.

#2—I use the term “Spirit” throughout the book, which is interchangeable with Higher Power, Universe, Source, Sacred, and the Divine—though there are many other names. What I am referring to is the existence of and connection to something bigger than ourselves to which we all belong. There are folx* who call it God or Allah, some Indigenous tribes who call it the Great Mystery, others who prefer not to name it at all. I encourage you to insert whatever word best aligns for you.

#3—For the sake of clarity and space, I often use the umbrella term “Black, Indigenous, and people of color” (BI&PoC*) to refer to the diverse group of humxns* oppressed by white supremacy* as a result of being racialized as non-white (including multiracial folx). BI&PoC do not experience racism* identically or uniformly, particularly Black and Indigenous folx, which is why they are separately identified from PoC*. Still, I believe that BI&PoC can have sufficiently common experiences such that we resonate with the overarching oppression* caused by white supremacy, so long as we also acknowledge the key differences between our racialized experiences. I have referred to specific racial identities where it made sense to do so.

#4—I use African American Vernacular English (AAVE)* throughout the book (because, well, I’m Black!), and I honor and acknowledge the Black American, predominantly queer* and transgender*, communities that created it. My use of AAVE is not license for any non-Black person to do so and I implore you not to, as explained in the glossary and Chapter 10.

#5—I’ve done my best to use inclusive language as I understand it at the time of publication, though all words are subject to questioning in terms of their inclusivity and who finds them inclusive. For the sake of brevity I have used “women+”* to connote all women, whether cis* or trans, as well as femmes*, femme-passing folx, and those of any gender identity* who face misogyny like women with an understanding that these identities are in no way binary (peep the glossary for the full definition and the corresponding definition for men+*). I’ve used specific gender identities when referring to some but not all (i.e., women, femmes, etc.). Lastly, when I refer to “man,” “woman,” “male,” or “female,” I do so with the understanding that both sex* and gender identity are social constructs. We’ll get into all this soon!

#6—I cannot and will not speak for all Black people (because we’re not a monolith), nor will I hold myself to that standard. Neither should you.

#7—White supremacy is complex, entailing multiple forms of oppression. It is first and foremost a form of racial oppression including anti-Blackness* and anti-Indigeneity, but it also includes heteropatriarchy*, homophobia, transphobia, classism*, ableism*, ageism, fatphobia*, xenophobia, anti-Semitism, and all forms of oppression. As such, I believe racial justice* includes ending all forms of oppression. BI&PoC include all ages, abilities, ethnicities, classes, sizes, religions, cultures, etc., so we cannot advocate for the freedom of some without advocating for the freedom of all. Instead of naming each of these forms of oppression separately, they are included within my references to white supremacy, though, for clarity, I’ve made explicit references in some cases.

#8—I believe Black and Indigenous liberation is the key to collective freedom. My intention is to call out* harms against all BI&PoC of all identities, but I will focus on those most oppressed. Prioritizing Bla

ck, Indigenous, queer, trans, disabled*, fat*, poor*, dark-skinned, non-English-speaking, immigrant, elder, etc. women+ (i.e., those living at the most oppressed intersectional identities) is how we can best help create freedom for us all. We are certainly having separate experiences, but we are not actually separate.

Let’s dive in!

PART ONE

GOIN’ IN FOR DA WIN

Love and Justice are not two. Without inner change, there can be no outer change. Without collective change, no change matters.

—REVEREND ANGEL KYODO WILLIAMS SENSEI

Getting Intentional

Before getting into this critical work, it is imperative to get clear on why you are here. This helps you to check if you’re showing up for authentic reasons and serves as an anchor you can return to whenever shit gets hard (and trust me, it will!).

Read the affirmation below, and when you’re ready, write or otherwise record your answer as a stream of consciousness.

Note whatever comes and then review, revise, and cut down as necessary until you have a clear, concise statement that you can return to as you move through this work.

I AM READY TO LEARN ABOUT SPIRITUAL ACTIVISM*, FIGHT WHITE SUPREMACY, AND DO BETTER BECAUSE:

ONE

Me, Myself & I

I’m going to tell it like it is. I hope you can take it like it is.

—MALCOLM X

For most of my life my biggest fear about addressing white supremacy was being rejected and abandoned for naming the realities of my oppressed experience as a queer Black woman, which has come to fruition more times than I care to recall. I have personally spent a lifetime feeling alone and misunderstood. I struggle to find places that accept me as my whole Black womanly self and people willing to listen and engage with my truth—one steeped in navigating a white supremacist world as the pervasive “other.” From the tender age of four, I was aware of being treated differently due to my Blackness and girlhood. At day care, my white “caretakers” locked me outside in the pouring rain all alone. In kindergarten, my white teacher attempted to hold me back a year (from kindergarten!), explaining to my white-passing* mother, who the teacher erroneously assumed had adopted me, that my Black brain just wasn’t as large as my white classmates’. It was a sentiment derived from her teachers’ manual, and in the year 1989 this educator deemed it solid ground from which to assume I lacked the intellect required to, I dunno, play with friends or say my name!? It was fucking despicable. And racist. Luckily, my mother was having none of it, and I was placed in a first-grade class after she threatened to sue the school board. Though I only knew about this incident after my mother shared it with me in adulthood, I distinctly recall knowing that I had to prove my intellect to others from first grade onward. That those around me—be it teachers, administrators, or friends—would assume that I was slow because I was a Black girl. I would look around my mostly white classroom and feel myself caged within four walls void of safe spaces, tangible or otherwise. Nobody looked like me and no one cared to understand me or my experience. I felt entirely alone, like an ugly duckling—deemed visibly undesirable and socially unsavory. Often remaining silent for fear of saying or doing anything to garner my Black body unwanted criticism, I disconnected from myself and my surroundings. Internalizing my heartbreak at being subjected to an onslaught of stereotypes, I vowed to excel and exceed all expectations of me whenever and however I could. I thought I could accomplish my way out of the Black box I had been placed in and became completely committed to controlling the narrative my white community had created for and about me. To try to achieve my way out of a form of discrimination I did not and could not yet grasp was deeply entrenched in the hearts, minds, and institutions of all those in my midst. Needless to say, I was continuously disappointed by the impact of my efforts, and with few resources to make sense of it all at just five years old, I assumed the oppression I faced was of my own making. That I was treated and perceived differently by all those in my community, including people I loved, because I was the problem. Growing up in Western Canada also meant being constantly compared with Black Americans. I was referred to as African American by non-Black folx for most of my upbringing—another way of being othered. But the truth is, the only place I felt truly free to be myself was visiting my auntie, uncle, and cousins in Washington State. A mere two-hour drive south presented an alternate universe full of Black love, Black food, and Black pride. I didn’t know the extent at the time, but these glimmers of Black American joy were my salvation.

As a Black girl from a financially insecure, single-mom-led home, the culmination of my stereotypical existence with the racist rhetoric of white supremacist status quo* left me feeling incapable, unworthy, and undeserving. My Blackness made whiteness* uncomfortable, and I was treated as the culprit for white folx’ discomfort—continuously made to feel too loud, too emotional, too boisterous. I learned to tone myself down. To keep quiet, play it safe, and never, ever speak my truth or prioritize my comfort or well-being above that of my white counterparts. In the rare moments I veered off course I was met with racialized harm in the form of emotional violence*, which rocked me like a kick to the head. Sticks and stones have never broken my bones, but words have really, really hurt me. I shrunk into the sliver of space deemed acceptable for a Black girl+* in a white world. It’s a survival skill that stuck with me in all facets of my personal and professional life, and one I continue to process and unlearn three decades later. One of the many privileges afforded to white people by white supremacy is the ability to simply be who they are without preconceived negative stereotypes regarding intellect, ability, class, criminal history, language, origin, or otherwise thrust upon them strictly due to the color of their skin. From as far back as I can remember I have longed to walk into a room and be acknowledged for who, rather than what, I am. To simply be “Rachel” before being “a Black woman.” But that is not my reality.

Reflecting on this now fills me with unimaginable anguish. I yearn to reach out to that little girl who felt alienated and isolated for nothing more than breathing while Black and femme. I want to hold her and let her know she is not wrong, but the system sure AF is. I want to shake my white teachers, friends, and friends’ parents and demand that they address their misogynoir* and stop causing this Black child so much harm. Mostly, I want to tell my younger self that though she deserves better, this is how white supremacy works. It breaks young BI&WoC* down so early and efficiently that we often spend a lifetime swimming in a cesspool of trauma, self-hate, and internalized oppression*.

The racist assumptions and stereotypes like those I endured from toddlerdom are not abnormal, quite the opposite. They are, as white supremacy is, entirely run of the mill. White supremacy is not merely white men running around in white hoods in the woods. No, it is the air we all breathe, and more of us—more white people in particular—are finally taking note of its stench. It is intentional and, often, unintentional. Individual and collective, permeating every institution the world over, from health and education to military and politics, and the impact begins from youth. The Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality’s 2017 report contains data showing that “adults view Black girls as less innocent and more adult-like than their white peers, especially in the age range of 5–14.”1 Black girls receive harsher punishment at school compared with their white peers and are further perceived as needing less nurturing, less protection, less support, and less comforting and as being more independent and knowledgeable of adult topics than white girls of the same age.2 In sum, Black girls are not viewed as girls by society at all. In Canada, young Indigenous girls are twenty-one times more likely to die by suicide than their white counterparts, with several Indigenous communities declaring states of emergencies as a result of the ongoing suicide epidemic.3

Clearly, I’m not alone in enduring the pain of white supremacy from early childhood. Black and Indigenous girls+ are not getting the support they desperately need and deserve, and this is due in part, if not

entirely, to systems of colonialism* and patriarchy* that have stripped us of our childhood and deemed us less worthy of care. Millions of melanated girls+ like myself have grown up ostracized and oppressed because of the color of our skin, and millions more still will unless we, as a collective, do something to change the oppressive systems as they currently exist.

The truth is that to be Black or Indigenous and a woman+ is to be in a state of constant grief* and rage. As James Baldwin said, “To be a [Black person] in this country and to be relatively conscious, is to be in a rage almost all the time.”4 Consciously and unconsciously, I’m infuriated over the reduced pay I earn for doing the same work as my male and white women and femme counterparts. I mourn the ability to express myself without being automatically discounted for being angry, to simply have my words received. I am traumatized by the frequent accusation of being overly dramatic when I name misogynoir. I’m enraged by a culture that still purports “all lives matter,” and I grieve over the racist shit my well-intentioned white friends spew out all too often. This is not a pity party, for the record, it’s just the facts of my life and the lives of so many other Black women+. Facts that are too often dismissed. Stop telling BI&PoC our experience is a damn illusion. It’s not.

Do Better

Do Better